Executive Summary

Allocating savings between taxable accounts and 401(k)s significantly impacts retirement flexibility and tax efficiency. While 401(k)s offer tax deferral and employer matches, all withdrawals are fully taxable, and withdrawals before age 59½ incur a 10% penalty. Analysis of four account allocation models across four different scenarios shows that a strategy of contributing to the 401(k) up to the employer match and investing the remainder in a taxable account, consistently maximizes net balances, preserves tax-deferred growth, and provides liquidity for large or unexpected expenses, making it the most effective approach for early retirement readiness and for handling various contingencies in life.

Introduction

Many individuals invest in employer-sponsored retirement accounts, such as a 401(k), but often it becomes their only significant financial asset. While 401(k)s and other employer-sponsored retirement accounts offer tax-deferred growth and employer matches, these benefits come with restrictions. Withdrawals made before age 59½ incur not only ordinary income taxes but also a 10% penalty.

Contributing all of one’s savings to a 401(k) can limit financial flexibility before retirement age, making it harder to retire early or cover large one-time expenses. By contrast, allocating part of one’s savings into taxable investment accounts provides greater flexibility, while still capturing the advantages of 401(k).

This article illustrates how different account allocation choices affect financial flexibility, tax consequences, and early retirement readiness under common life situations. By holding most assumptions constant, such as income, contribution levels, and investment returns, we can isolate the impact of where contributions are allocated: in a taxable account, a tax-deferred 401(k), or a mix of the two.

We will present four different scenarios to test the performance of four account allocation models. The results suggest that the strongest approach for preparing both for early retirement and for handling large expenses is to place most assets in taxable accounts while still taking full advantage of the 401(k) employer match. However, the best allocation ultimately depends on personal circumstances such as career stability, health, and lifestyle choices.

Four Allocation Models and Scenarios

The following are descriptions of four allocation models. In this article, allocation refers to the accounts into which contributions are invested, not how they are divided among different asset classes, such as in stocks and bonds:

- All-in-Taxable: All contributions are invested in a taxable account

- All-in-401k: All contributions are invested in a 401(k)

- 1-to-1: Contributions are split 50/50 between taxable and 401(k)

- 2-to-1: Contributions are split 66/34 between taxable and 401(k)

We will test how these portfolios perform in four different scenarios:

| Scenario | General Explanation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Retire-at-67 | The individual works full-time from age 30 to 67, the full Social Secuity age. | Serves as the baseline scenario to understand the advantage of the 401(k), specifically the impact of employer match. |

| Retire-at-50 | The individual retires early at age 50 after 20 years of full-time work and begins annual withdrawals of $40,000. | Evaluates how different portfolios perform when retirement occurs earlier. |

| WorkPT | After retiring at 50, the individual earns $30,000 annually from part-time work while making annual withdrawals. | Explores the impact of the tax consequences that part-time income has on portfolio withdrawals and balances. |

| HouseDeposit | A one-time $100,000 withdrawal is made at age 40 in addition to the WorkPT scenario. | Assesses how large, unexpected expenses affect portfolio balances and retirement preparedness. |

We assume that the full-time income is $100,000 and the out-of-pocket contribution is $23,500. This contribution amount is the 2025 annual employee contribution limit. The income is set at $100,000 so that the remaining gross income of $76,500 after the contribution is sufficient to cover basic necessities.

Further, we assume that all four portfolio allocation models yield a 5% annual real return (after-inflation return), so that the final balance can be referenced against the value of money today.

In the taxable account, we assume a 2% dividend yield, with dividends taxed at the ordinary income tax rate. Further, when long-term gains are realized in the taxable account, we assume that 40% of the assets sold are taxable. These tax rates vary depending on the scenarios and are deducted from the taxable account.

In the 401(k), all withdrawals are taxable, since this is a tax-deferred account with zero cost basis (no tax was paid on the deposit). The amount of tax owed varies depending on the scenarios. Further, there will be a 10% penalty for any withdrawals before the age of 59½. These taxes and penalties are deducted from the 401(k).

The taxes and penalties in these accounts also incur additional taxes and penalties. However, for simplicity, we assume that they are paid from cash on hand.

Results from Four Scenarios

Retire-at-67

The Retire-at-67 scenario simulates a situation in which an individual saves entirely either in the All-in-Taxable allocation or in the All-in-401k allocation.

In both cases, the individual contributes the same out-of-pocket amount of $23,500, corresponding to the maximum employee contribution to a 401(k). The key difference between the All-in-Taxable and the All-in-401k allocation is that the latter includes a 5% employer match. For an income of $100,000, this match amounts to $5,000.

In this Retire-at-67 scenario, the individual works from age 30 until age 67, then retires and begins receiving Social Security benefits. Age 67 is the current full retirement age for Social Security purposes.

Although the out-of-pocket contributions are the same, the All-in-401k allocation naturally accumulates a higher balance than the All-in-Taxable allocation at age 67 due to the employer match.

Due to the compounding effect of the employer match, the ending balance for the All-in-401k allocation of approximately $2.27 million at age 67 is over 40% greater than the All-in-Taxable allocation.

This Retire-at-67 scenario is relevant for individuals planning to work until full retirement age, assuming job security sufficient to withstand economic, political, and technological changes.

However, some individuals may not be able to work full-time for 35 – 40 years due to career disruptions, declining health, or family responsibilities. Others may choose to retire early despite being able to continue working, either stopping completely or working part-time on their own terms. We explore these situations next.

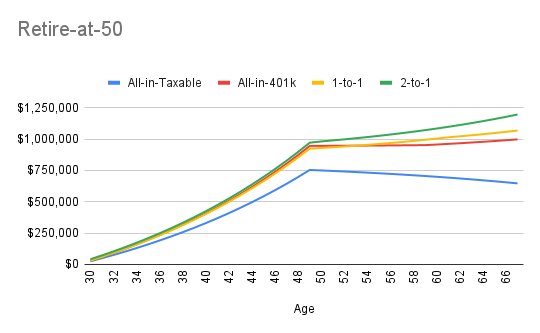

Retire-at-50

The Retire-at-50 scenario examines a situation in which the individual retires after 20 years of full-time work. As in the Retire-at-67 scenario, work begins at age 30, but retirement occurs at age 50.

In addition to the All-in-Taxable and All-in-401k allocations, we include portfolios that split between the taxalble and 401(k) accounts. The first mixed portfolio, the 1-to-1 allocation, invests $11,750 (50% of $23,500) in each account. The second mixed portfolio, the 2-to-1 allocation, invests $15,666 (66% of $23,500) in the taxable account and the rest, $7,833, in the 401(k).

All other assumptions, including income, employer match, and rate of return remain the same as in the Retire-at-67 scenario.

From age 50, the individual withdraws net cash of $40,000 annually, an amount sufficient for a modest single-person lifestyle. The exact withdrawals depend on the tax treatment of each account. For example, taxable accounts may incur long-term capital gains taxes, while 401(k) withdrawals are fully taxable. To net $40,000, withdrawals must cover taxes owed. These taxes will be deducted from the portfolios.

The All-in-401k allocation results in a higher balance than the All-in-Taxable account, due to the employer match, even after the 10% early withdrawal penalty before age 60.

Splitting contributions between taxable and 401(k) accounts yields interesting results. For the 1-to-1 allocation, the ending balance at age 67 is 7% higher than the All-in-401k portfolio. For the 2-to-1 allocation, the ending balance is approximately 20% higher.

| All-in-Taxable | All-in-401k | 1-to-1 | 2-to-1 | |

| All-in-Taxable | – | -35% | -39% | -46% |

| All-in-401k | 54% | – | -7% | -17% |

| 1-to-1 | 65% | 7% | – | -11% |

| 2-to-1 | 85% | 20% | 12% | – |

These outcomes partly arise from the different in tax consequences between taxable and 401(k) accounts. Assuming capital gains are the only income besides dividends, the individual benefits from a 0% long-term capital gains tax, as income remains below the $48,350 threshold for the 15% rate.

In the 1-to-1 allocation, withdrawals come first from the taxable account until it is depleted at age 61, then from the 401(k) starting at age 62 penalty-free. In the 2-to-1 allocation, the $40,000 annual withdrawal can be fully covered by the taxable account, allowing the 401(k) to grow tax-deferred, which explains its superior performance.

Retire-at-50 scenario assumes full retirement at age 50 with no work income thereafter. However, some individuals reduce work hours rather than stopping entirely. We explore these cases in the two other scenarios that follows.

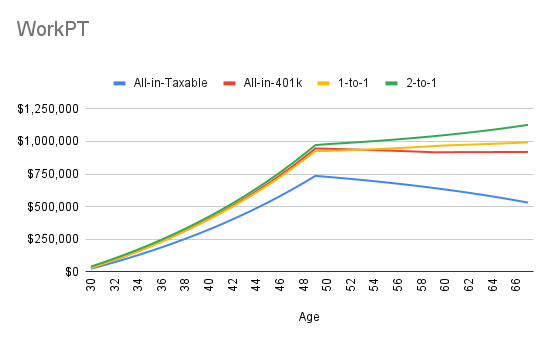

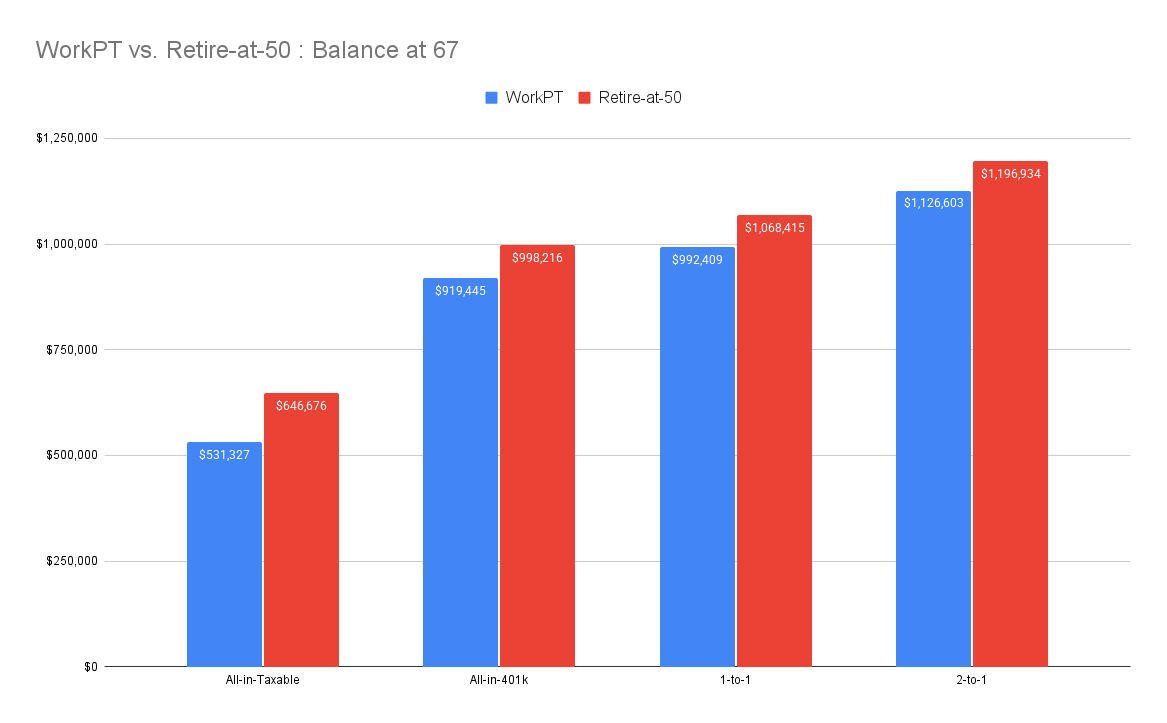

WorkPT

In the WorkPT scenario, the individual earns $30,000 annually from part-time work after retiring from full-time work at age 50, while all other assumptions mirror the Retire-at-50 scenario.

Mixed allocation portfolios (1-to-1 & 2-to-1) outperform All-in-Taxable and All-in-401k allocations. This outperformance is more pronounced in the WorkPT scenario than in the Retire-at-50 scenario, although the final balances for the former is lower than the latter due to tax consequences.

This higher balance results from the higher taxes on withdrawals affected by part-time income in the WorkPT scenario. The marginal tax rate for 401(k) withdrawals jumps from 12% in the Retire-at-50 scenario to 22% in the WorkPT scenario. In the Retire-at-50 scenario, taxable account withdrawals incurred no long-term capital gains taxes, while 401(k) withdrawals were taxed atand gains in the taxable account are now subject to the long-term capital gains rate of 15%.

| Incomes/Taxes | Effective Rate | Marginal Rate | Cap. Gains Rate |

| $40k (Retire-at-50) | 7% | 12% | 0% |

| Last $40k out of $70k (WorkPT) | 14% | 22% | 15% |

While the ending balance is lower for all four allocation models in WorkPT, the outperformance of the mixed models, especially the 2-to-1 allocation against other models, is greater compared to the Retire-at-50 scenario. For example, the 2-to-1 allocation performed 23% better than the All-in-401k allocation (compared to 20% in Retire-at-50). This difference arose from the fact that the 2-to-1 allocation did not withdraw from the 401(k) at all until age 67 in both WorkPT and Retire-at-50 scenarios, but in the former, the marginal tax rate for withdrawals from the All-in-401k allocation was 22%, while in the latter it was 12%.

| All-in-Taxable | All-in-401k | 1-to-1 | 2-to-1 | |

| All-in-Taxable | – | -42% | -46% | -53% |

| All-in-401k | 73% | – | -7% | -18% |

| 1-to-1 | 87% (65%) | 8% (7%) | – | -12% |

| 2-to-1 | 112% (85%) | 23% (20 %) | 14% (12%) | – |

Depending on living expenses, after Social Security, all portfolios may cover essentials such as housing, healthcare, and food. The 2-to-1 allocation provides the most secure retirement.

Although adding $30,000 part-time income provides a more realistic scenario and shows the effects of higher marginal tax, these portfolios have not yet been stress-tested for large withdrawals.

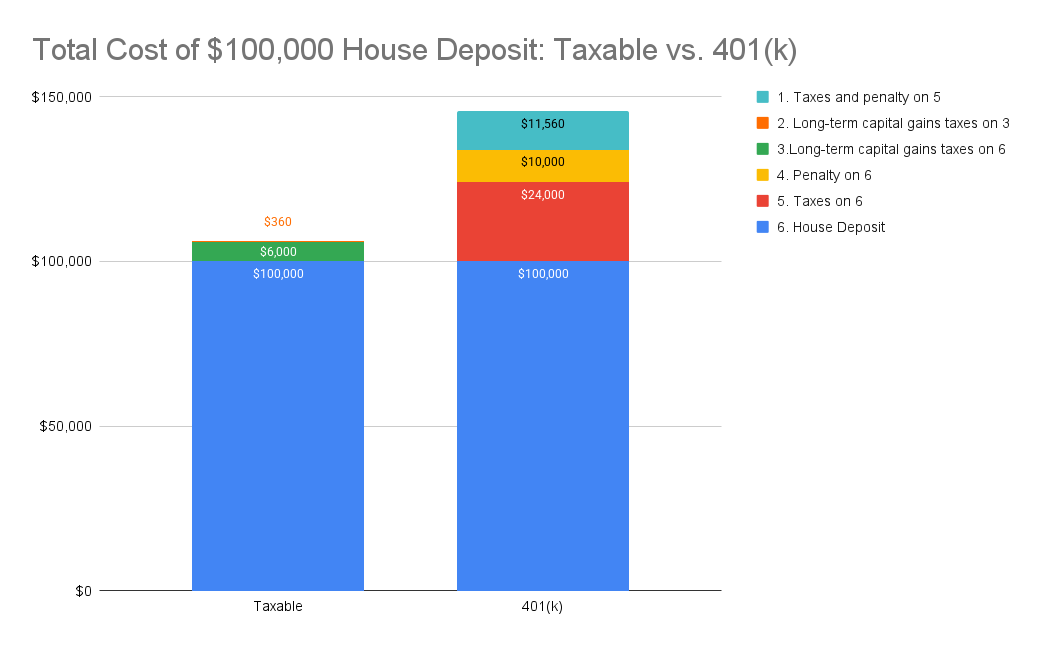

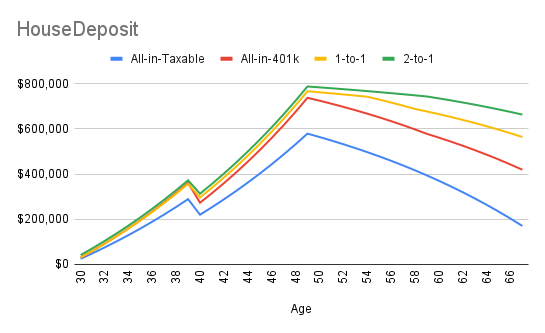

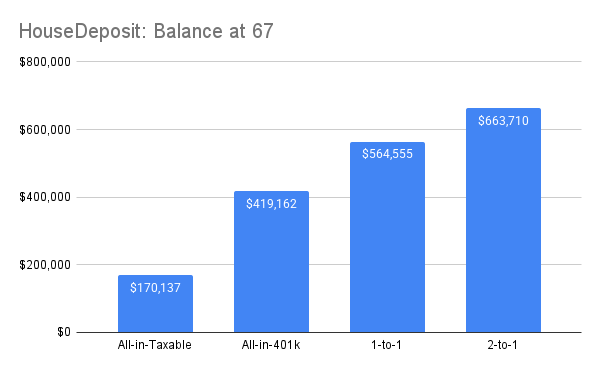

HouseDeposit

In the HouseDeposit scenario, a $100,000 house deposit occurs at age 40. Given that buying a house is a common life event, as over 65% of Americans are homeowners, this scenario examines portfolio performance under a large, one-time expense.

Except for the All-in-401k portfolio, the $100,000 withdrawal comes from the taxable account. In the 2-to-1 allocation, the taxable account lasts until age 60 before 401(k) withdrawals begin penalty-free. In the 1-to-1 allocation, the taxable account lasts until age 54, requiring four years of 401(k) withdrawals with penalties from ages 55–58.

The key factor is tax consequences. At age 40, while still earning $100,000, withdrawing $100,000 from a 401(k) incurs a 24% marginal tax, costing $145,560. From the taxable account, the cost is only $106,360 due to the long-term capital gains tax.

Under this scenario, the all-in-taxable portfolio fails to provide retirement security, ending with roughly $170,000 at age 67. The All-in-401k portfolio ends with about $420,000, which may be also insufficient even with Social Security.

The outperformance of the mixed portfolios in the HouseDeposit scenario, compared with All-in-Taxable and All-in-401k, was much greater than in the WorkPT scenario. The 2-to-1 allocation outperformed All-in-Taxable by 290%, versus 112% in the WorkPT scenario, and outperformed All-in-401k by 58%, compared with 23% in the WorkPT scenario.

| All-in-Taxable | All-in-401k | 1-to-1 | 2-to-1 | |

| All-in-Taxable | – | -59% | -70% | -74% |

| All-in-401k | 146% | – | -26% | -37% |

| 1-to-1 | 232% (87%) | 35% (8%) | – | -15% |

| 2-to-1 | 290% (112%) | 58% (23%) | 18% (14%) | – |

The best-performing portfolio is the 2-to-1 allocation, ending around $660,000 arguably the only allocation that is ready for early retirement. If the Social Security income were $30,000, with portfolio withdrawals of $25,000, equivalent to a 4% safe withdrawal rate, the individual could maintain a $55,000 annual lifestyle, covering basic necessities but limited discretionary spending.

Between the mixed allocation of 2-to-1 and 1-to-1, the former was able to avoid any early withdrawals from the 401(k), allowing those funds to continue compounding tax-deferred until penalty-free access began at age 60. By contrast, the 1-to-1 allocation required accessing the 401(k) earlier, triggering both taxes and penalties, which reduced overall efficiency and long-term growth.

What all four allocation models have in common is that the balance at age 50, when the individual retires early, is too small to generate $40,000 in net cash per year without beginning to deplete the portfolio.

While we assumed that the $30,000 income from part-time work was not invested, it could be added to investment accounts to achieve more secure portfolios than those in the HouseDeposit scenario.

Conclusion

These exercises highlight that deposit allocation significantly affects outcomes, especially for early retirement or large expenses like home purchases. Although 401(k) is an excellent saving vehicle for retirement for its tax-deferral and employer match, overreliance on it limits flexibility.

A best practice is to contribute to the 401(k) only to maximize the employer match, and allocate remaining contributions to a taxable account, as the 2-to-1 allocation model showed.

While these findings show the possibility of early retirement with the right account allocation, they apply primarily to a single individual. For a household with dependents, one would need to either significantly increase contributions and incomes, potentially doubling them, which can be challenging for many, or delay retirement until there are sufficient financial assets.

Regardless of the situation, knowing the right account allocation strategy for portfolio resilience allows one to handle various contingencies in life more effectively.

Schedule a call with me here.

The information provided in this blog post is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. It is not intended as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any financial product, and I do not promote any organizations.