“With whole life insurance, not only can you protect your loved ones with death benefit, you can accumulate assets for yourself, called cash value. In addition, you will receive guaranteed 5% dividends, and you can access your assets anytime tax-free, in the form of a loan. This feature is unlike a 401k, which you have to wait until retirement to make distributions, and will be taxed. You essentially become your own bank, a strategy used by many extremely wealthy individuals, like Bush and Rockefeller families who have built generational wealth.”

Upon hearing such a pitch from an insurance agent, aspiring individuals may mistakenly consider insurance, a contractual agreement drafted in insurance companies’ favor, to be a versatile do-it-all financial asset, and a ticket to the upper class. When something sounds too good to be true, there is usually a catch, and whole life insurance is no exception. The following analysis highlights three reasons it is not suitable for individuals who are just beginning to accumulate wealth, and suggests alternatives to whole life insurance to protect heirs and accumulate financial assets.

Reasons to Avoid Whole Life Insurance

1. Exorbitant fees

Insurance agents earn their livelihood through commissions. They prefer to sell whole life insurance over other products as it is most lucrative for them. Although the commission structure varies depending on the company and product, it is typically 100% of the premiums in the first year. Consequently, policyholders can start building cash value, the investment portion of the policy only in the second year of the contract. Further, insurance products often entail high ongoing management fees.

Insurance management expenses are inherently high owing to the unduly complex nature of the products. Whole life insurance, in particular, encompasses various elements including premium, death benefit, and cash value, some of which can change based on one’s age, health condition, and gender. These multifaceted components among others collectively constitute one product, necessitating a team of professionals for management, thereby inflating management expenses, eroding the performance of investments.

2.Fictitious dividends

One of the perceived appealing features of whole life insurance is its guaranteed dividend payments. However, these guaranteed “dividends” policyholders receive are not akin to dividends from conventional investments. Rather, they are merely a return of deliberately overcharged premiums. Insurance companies allocate a portion of premiums for unforeseen expenses as contingency funds, from which policyholders have a right to receive a share of the surplus.

Since they are not cashflows generated from investments, it renders the term “dividends”, a misnomer. Nonetheless, they can call it so since the IRS explicitly states these overcharge in premiums to be rebated as dividends. This tax code serves to relieve insurance companies from acting transparently.

Such an adversarial arrangement for policyholders means they must rely on the portion of the premiums that are actually invested to perform extremely well, to compensate for the numerous commissions and fees they pay. The reality is that it would be considered fortunate if the cash value of their policy exceeds the total premiums paid.

3.Misleading concept of “Infinite Banking”

Another perceived benefit of whole life insurance is its tax-free growth and access to its cash value. While it is accurate that cash value accumulates tax-free and policyholders can access it in the same manner, the impact of reduced investment performance as a result of prohibitive fees often outweighs the advantages of these favorable tax treatments.

Moreover, the feature, which allows policyholders to access their cash value, is misleadingly marketed as “infinite banking” or “becoming your own bank.” It is deceptive, because one can make withdrawals anytime from conventional brokerage accounts such as taxable individual and joint accounts in firms including Fidelity and Charles Schwab, as well as many other non-bank financial accounts. In the case of whole life insurance, policyholders can access cash value only through loans rather than withdrawals. Since they are loans, insurance companies charge interest on the money policyholders contributed themselves, which adds to the overall cost of the policy.

This arrangement effectively makes insurance companies the owner of the cash value. Consequently, they can place limits on how much money policyholders can access at a time, which contradicts the concept of “infinite banking” suggested by its name. If policyholders use insurance as their primary savings vehicle, this restriction will prevent them from covering significant expenses including unforeseen medical costs and large mortgage payments, potentially leading to detrimental outcomes. Additionally, taking out loans against the cash value will diminish the death benefit.

Who whole life insurance is for

These features demonstrate insurance contracts are structured in a way that the vast majority of policyholders do not benefit. Particularly in whole life insurance, people with modest means who lose out are essentially compensating affluent individuals who have the means to see out the contracts and receive death benefits, who may not necessarily need life insurance in the first place.

Typically, these individuals are already financially secure, possessing assets in investment brokerage accounts, owning paid-off properties, and having excess funds that can be allocated to insurance without causing any financial strain. Given their financial position, there is a high probability that their heirs will receive death benefits.

In light of the significant financial commitment whole life insurance requires, it is crucial to understand that it is not for the average individual and certainly not a savings vehicle. Despite its unsuitability, insurance agents often sell it to individuals who cannot afford it, often by suggesting falsely how eminent figures have built generational wealth using life insurance. Renowned American families like the Bushes and Rockefellers, most likely own life insurance products such as whole life insurance. However, they primarily amassed their fortune through businesses. Their wealth is diversified across various assets, including businesses, stocks, bonds, and real estate, with life insurance constituting only a small portion of their enormous wealth. Drawing comparisons with magnates like them is not practical for the average person seeking financial stability.

How alternatives to whole life insurance compare

Whole vs. Term life insurance

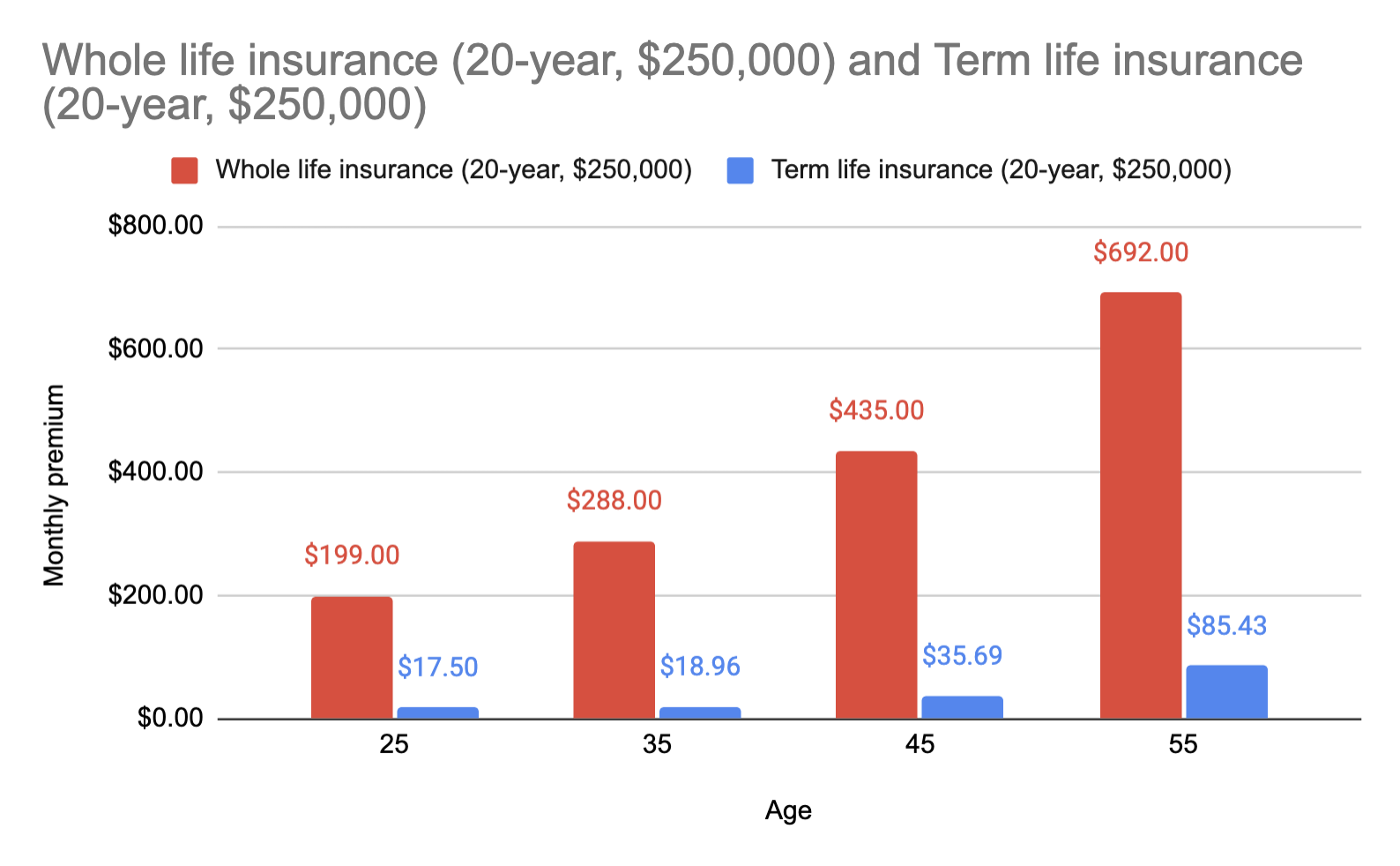

For the ordinary person without tens of millions of dollars in liquid assets, term life insurance is sufficient to protect their loved ones. It provides coverage for a specific period, such as, ten, fifteen or twenty years, ensuring that beneficiaries that may include the policyholder’s children are protected until they have the ability to become financially independent. While a drawback of term life insurance is that it lapses once the term ends, it remains a considerably more affordable option compared to whole life insurance, often costing over ten times less.

Due to the affordability of term life insurance for average individuals, they can sustainably keep the policy in force compared to whole life insurance. Discontinuing premium payments for whole life insurance typically results in only receiving back the poorly-performed cash value, having wasted a considerable amount of money that could have been better deployed elsewhere. While insurance agents may mention how making premature distributions from retirement accounts such as 401k incurs penalties, terminating a whole life insurance policy during the surrender period can also lead to hefty penalties. This surrender period can last up to 15 years, and if it is shorter, the premium will be higher.

Whole life insurance vs. Conventional Investments

Holding an inexpensive term life insurance means one would have room to allocate funds to build assets. The expenses associated with investing in low-cost mutual funds in platforms including Fidelity and Charles Schwab represents only a small fraction of those of whole life insurance. In the long-term, one can build assets greater than the face value of whole life insurance, which is its death benefit.

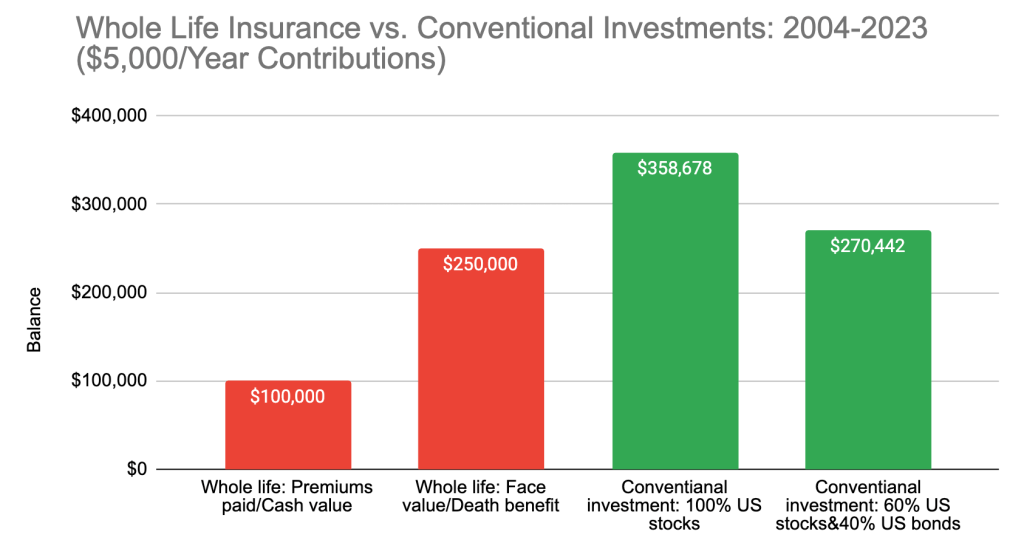

The graph below shows a comparison between whole life insurance and conventional investments in non-insurance brokerage accounts. If the whole life insurance policyholder made $5,000 annual premium payments, which is approximately the average premium payment made for a product whose face value is $250,000, for 20-years from 2004-2023, the total premium payment would have been $100,000.

Due to the complexity, variability and elusiveness of individual contracts, it is difficult to make an accurate estimate of how much cash value in a whole life insurance policy will be. Considering the high cost of the policy and the fact that not all premiums are invested, this comparison assumes that the total premium paid equal the cash value, although this may not always be the case. In addition, if the policyholder deceased at the end of the 20-year period, there will be a death benefit payout of $250,000. However, with the death of the policyholder, the cash value will be void.

In contrast, if one invested $5,000 a year in an all-US stock portfolio for twenty years in the same time frame, the ending balance would have been $358,678. Alternatively, a portfolio with more conservative 60% US stocks and 40% US bonds would have amounted to $270,442. These figures significantly surpass the accumulated $100,000 cash value and even exceed the $250,000 death benefit. These comparisons highlight the superior performance of conventional investments over whole life insurance. However, the benefits of these investments extend beyond numerical measurements to include intangible aspects.

What people may overlook is the stress whole life insurance may cause to the beneficiaries of the policyholder. It is highly plausible that in the years leading up to the policyholder’s death, the individual may become incapacitated, resulting in increased medical expenses and potentially reducing his or her ability to pay the monthly premiums. The beneficiaries of the contract could be under tremendous stress, worrying whether or not they can keep the policy in force, in addition to facing the impending loss of a family member. In contrast, investing in conventional investment accounts will not involve similar emotional distress. Heirs and other loved ones can bid farewell to the passing relative in a dignified manner without the added worries of financial matters.

Ending remarks

Although this article presented critical perspectives regarding whole life insurance, it is important to acknowledge that individuals who consider purchasing it often do so out of a genuine concern for the well-being of their heirs. Such attitudes reflect their deep sense of responsibilities for their loved ones.

However, aspirations that may be present in the decision-making process can cloud one’s judgment. This desire for upward mobility can lead individuals to purchase unsuitable financial products that give them a sense of glamour, but not financial stability. In reality, whole life insurance is to a financial product what the likes of Hermes and Louis Vuitton are to consumer goods. While these items are suitable for purchase only by truly affluent people, half of their consumers are those without sufficient means. This highlights the importance of monetary education and seeking guidance from qualified fiduciaries when organizing their finances.

Continue the conversation with me here.